Following the Boston marathon bombings many articles have been written about the swift medical response that occurred and the extraordinary efforts that saved lives. Reading 'Why Boston's Hospitals Were Ready' by Dr. Atul Gawande, this blogger was struck by one aspect of the story:

Per Dr. Gawande "... There’s a way such events are supposed to work. Each hospital has an

incident commander who coordinates the clearing of emergency bays and

hospital beds to open capacity, the mobilization of clinical staff and

medical equipment for treatment, and communication with the city’s

emergency command center... no sooner had he set up his command post and begun making phone calls

then the first wave of victims arrived. Everything happened too fast

for any ritualized plan to accommodate.

So what did you do, I asked him.

“I mostly let people do their jobs,” he said. He never needed to call

anyone. Around a hundred nurses, doctors, X-ray staff, transport staff,

you name it showed up as soon as they heard the news. They wanted to

help, and they knew how. As one colleague put it, they did on a large

scale what they knew how to do on a small scale. They broke up into

teams of six or so people, one trauma team for each patient. A senior

nurse and physician stood at the door to the ambulance bay triaging the

patients going to the teams. The operating-room director handled triage

to, and communication with, the operating rooms. Another staff member

saw the need for a traffic cop and began shooing extra clinicians into

the waiting room, where they could stand by to be called upon....

... at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center... much the same experience there... “But everybody spontaneously knew the dance moves,” he said. He didn’t have to tell people much of what to do at all..."

OK, so one really can't complain about success and things were done extraordinarily well resulting in the optimum outcome... as is very often the case in healthcare. From Katrina to Sandy, and many incidents before, in-between and after, extraordinary efforts by ordinary (and extraordinary) people have often 'saved the day.' However, it is a realization that this has usually been the case (i.e. a reliance on extraordinary efforts plus often a good measure of luck) rather than planning, processes, and systems that has led to the adoption of systems and processes to respond to emergencies.

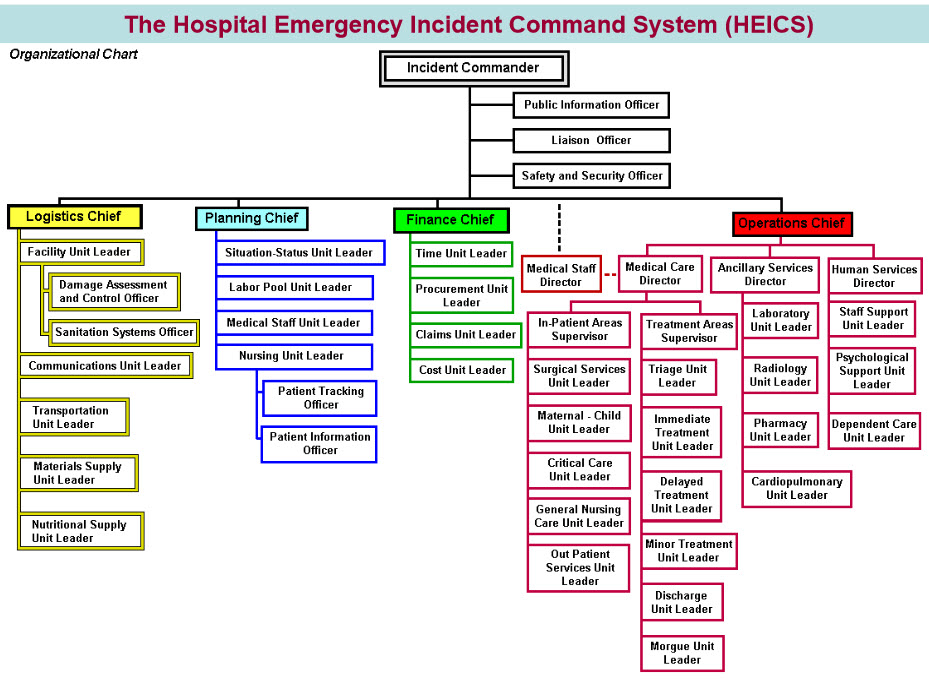

The Hospital Emergency Incident Command System is the standardized approach designed to help hospitals prepare for and respond to various types of disasters. Clearly this mass-casualty event was precisely the kind of emergency the system was put in place to deal with! Yet we read that these systems were never used, and that everyone immediately reverted to the 'every one pitch in and do what needs to be done' response that has long been typical of the response in health care! Indeed Dr. Gawande appears to dismiss the HEICS as a "ritualized plan" apparently much too slow to be of much use.

Thus although the medical response was a success, clearly the emergency response systems of the various Boston hospitals were found to be wanting... Some work is clearly needed there to ensure that they are more responsive and will work in any future emergencies. Although things ended up working out extraordinarily well on this occasion, they may not the next...

Dr. Gawande ends his article with: "... We’ve learned, and we’ve absorbed. This is not cause for either

celebration or satisfaction. That we have come to this state of

existence is a great sadness. But it is our great fortune. Last year, after the Aurora shooting, Ron Walls, the chief of emergency

medicine at my hospital, gave a lecture titled “Are We Ready?” In Boston, it turns out we all were."

Is this the right lesson to take from what happened? This blogger is not so sanguine.

Some other articles related to hospital response:

Note;It must be observed that the health care folks handled this much better than did the telecommunications sector.

No comments:

Post a Comment